These biographies have been compiled over seven years (2003-2009) from research comprising material from archives, two inquests, magazine and newspaper reports and articles, the TRC Report and the transcriptions of the hearings, books, interviews with relatives, and the internet. I apologise for any errors that may have crept in during the editing, and would appreciate receiving any information which could add to our knowledge of these men and the events which took place.

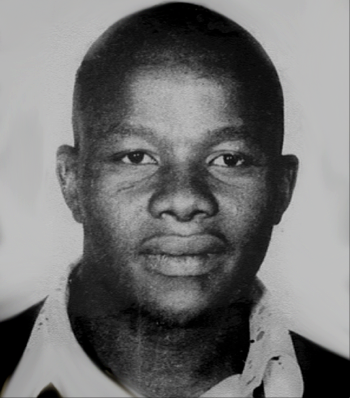

Sicelo Mhlauli Biography

Sicelo Mhlauli (b 25/5/1949) was headmaster of an Oudtshoorn school at the time of his death. He was active in the Oudtshoorn Youth Organisation and a community newspaper "Saamstaan". He was also a UDF member. Before his death he had been frequently detained, tortured, threatened and harassed.

He was on holiday when he died, aged 36. Matthew Goniwe and Sicelo had grown up in Cradock, just two years between them – they were great friends. Sicelo had just arrived back in Cradock for the school holidays and his wife, Nombuyiselo, was on a course in Port Elizabeth. He bumped into Matthew, who suggested he travel with them to PE.

It is believed that Sicelo wanted to collect Mbuyi in PE, and they would all travel back together to Cradock. Someone who was meant to travel with Matthew stood down from the car, and the four of them – Matthew Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sparrow Mkonto and Sicelo – left for Port Elizabeth. But the meetings went on late, and it was not possible to collect Mbuyi. The four men left PE at around 21h10 in the evening of the 27 June 1985, and were never seen alive again.

Sicelo was the second body to be found, many kilometres from Sparrow’s, and also from the burnt-out car. Mhlauli had 25 stab wounds in the chest, seven in the back, and another four in his arms. His throat had been cut. His right hand was missing. He had died from blood loss, predominantly from severed jugular veins. His body had extensive burns.

Mhlauli, a tall strong man, appeared to have struggled with his captives. Both he and Mkonto had been handcuffed and tied with rope. Nyameka Goniwe fears that while Sparrow and Sicelo’s bodies were found, Fort and Matthew were still being interrogated. People had scanned the area where their bodies were later found. Where Sparrow and Sicelo were found, there was petrol all around, the bodies were still wet, and there were lots of bloodstains. When Matthew and Fort were found, there were no signs of bloodstains.

A relative, Catherine Barayi gave harrowing testimony at how Sicelo’s hand was cut off. She first heard of his death when she saw television images of his charred and mutilated body.

In 1991, after President FW De Klerk announced a second inquest into the murders –after the military was linked to the murders through a Top Secret signal sent to the State Security Council just days before their murder – investigators went to Eastern Province Command to search for relevant documents, but found that a Military Intelligence (MI) team had already been through everything. MI said they were “investigating the leak of the signal”. A former police informant who came forward to investigators claiming she had vital information was asked to make a statement to MI, but claimed she felt compromised.

Self-confessed thief, prostitute and police informant Jennifer Du Plessis claimed her ex-lover, John Scott had told her that a “hand-picked” group of cops and SADF members led by a “Zac Edwards” had killed the Cradock Four after a roadblock. Scott, who was the administrative officer of the “Hammer” unit, claimed he had personally killed Goniwe.

The Hammer Unit was established by Brigadier CP “Joffel” van der Westhuizen in 1985 as a special forces unit to be used for “bona fide” military operations. They were meant to be the equivalent of the US Green Berets. Van der Westhuizen said the purpose of unit was “to enable a quicker response in anti-insurgency tasks, in protecting VIPs and national key points, and in dealing with landmines and other explosives”. While Van der Westhuizen claimed Hammer was not involved in the Goniwe operation, there are many contradictions that point to its involvement.

Former Hammer member Major Graham Lombard apparently knew something about the Goniwe operation. A severed hand was allegedly kept in a bottle in Lombard’s office, and was used to terrorise black detainees under interrogation. It was later destroyed when someone realised that the hand would have identifiable fingerprints.

The former commander of Hammer was Commandant Andries Struwig, who was in charge of the EP Command Reaction Force from 1983 until 1992. But all investigations into Hammer’s activities and operations ran into dead ends, and anyone investigating them had their lives threatened by unknown persons.

Little is known about military involvement in the struggles occurring in the Eastern Cape, and most records have been destroyed (many illegally), but what is know is that the military in Port Elizabeth used several “offices” for their activities, including a building at 22 Strand Street (Noma House), that the then-Department of Community Development had hired from 17 June 1982 until April 1987. From 1982 until 1987, Military Intelligence also occupied Bristerhuis, with it’s entrance in Main Road, and another entrance in Strand Street, now known of Victoria Kaai (an extension of Strand Street).

MI’s “opposition”, the Bureau of State Security used to operate from the 9th floor of Ford House, with the entrance in Main Street, since 1977.

But whoever had a hand in the murders, it was only seven men who applied to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for amnesty: five members of the Port Elizabeth Security Police, an army colonel and the notorious commander of the Vlakplaas police hit squad, Colonel Eugene de Kock, known amongst his colleagues as ”Prime Evil”.

The PE policemen were Security Police chief Colonel Harold Snyman, his deputy, Major-General Nicholas Janse van Rensburg, Captain Johan Martin "Sakkie" van Zyl, the man who allegedly led the hit squad, Lt Eric Alexander Taylor, Sgt Gerhardus Johannes Lotz, and SADF colonel Hermanus Barend du Plessis.

The seven began their testimony before Mr Justice Ronnie Pillay in Centenary Hall, Ntshekisa Street, Port Elizabeth, in February. Their amnesty applications detailed their version of the murders: Taylor said he and five others had staked out the PE-Cradock road. At about 10pm the car was spotted and they followed in two cars. Before Middleton they overtook the activists and blocked the road. Taylor said: “At about 23h00 on 27 June 1985 these four identified activists were intercepted in the vicinity of the Olifantshoek (sic) pass (it’s actually called Olifantskop Pass).

“(They) were transported together with Van Zyl, Taylor and Lotz to an area near St George Beach near Port Elizabeth, where (security policemen) Mgoduka, Faku and (askari) Sakati later joined us. The four men were handcuffed, separated and driven back towards PE under the impression they were being detained. The convoy turned off at Bluewater Bay, near the Scribante race track. (The black Security Policemen were murdered in 1989 by their white colleagues when they threatened to spill the beans).

Bloemhof farmer Mrs Dorris Butters and her driver Mr Ntonti Vusani said they had been stopped at a Security Forces roadblock near Bluewater Bay at 6.30pm on June 27, although there is no official record of the roadblock. They say the roadblock was on freeway near the Bluewater Bay off-ramp, and was the biggest roadblock she had ever seen. Police claimed the roadblock had been a week before.

Sicelo and Sparrow were abducted in one car, Matthew and Fort in another. Another cop drove the Ballade. Harold Snyman had told them: “It was between us. Nobody has to know about this except ourselves.”

After murdering Mkonto, Van Zyl went to a rendezvous with three black members of the Security Police, whom he had ordered to help with the murders. They left their minibus behind and travelled with Van Zyl. When they got to the body, he ordered Sgt Faku, a member of the PE Security Police, to stab the dead man and set the body on fire. The other black security policemen apparently with Van Zyl were Glen Mgoduka, and a turned ANC guerrilla, or Askari, called Xolile Shepherd Sekati.

Mhlauli had been beaten unconscious by Van Zyl Taylor, Mgoduka, Lotz and Faku before being stabbed to death.

The TRC heard many applicants tell them how authorisation for such irregular and illegal actions had been given at the highest level. One instance detailed how, at a meeting of the senior national and divisional leadership of the Security Police in early 1985, President PW Botha had told them to bring the situation under control by “whatever means possible”.

Further evidence of the condoning of illegal actions by junior officers by their political and police commanders was the “consistent failure to discipline”, the numerous cover-ups and “sweeping” that occurred after crimes were committed, in many instances by more senior policemen.

The TRC also said that while former president FW de Klerk and others had consistently denied knowing about illegal actions by the security forces, the TRC was struck by the fact that, in numerous cases, nobody appeared to have asked any questions. It showed a modus operandi and a line of command similar across the country, which encouraged a “culture of impunity”.

Lower ranks were also inducted into covert and unlawful operations by their commanders, which, combined with the heightened sense of being at war, a strong hierarchical structure in the Security Police, made those who were drawn into such operations feel privileged and honoured.

FW de Klerk’s suggestion that such activity was unauthorised and undertaken by “bad apples” does not hold up to the evidence before the TRC, which suggests that those in command of the Security Police were well aware of the existence and effectiveness of covert, illegal operations, and those with a long history of committing abuses were usually promoted and rewarded, and the political masters of these men did not stand by them and take responsibility for the abuses, but denied them instead.

The investigating officer was Warrant Officer SJ Els, who was sent to Veeplaas on June 28 1985 where he found a badly burnt body, which turned out to be Sparrow Mkonto. Els then went to Bluewater Bay where another burnt body had been found. This would turn out to be Sicelo Mhlauli.

Somerset East cops said they saw Matthew’s car leave Cookhouse at 1pm on Thursday 27 June. A reporter told Nyameka Goniwe that a body had been found. When people from Cradock went there to search, they were watched by a car. When they tried to follow the car, it drove away fast.

The families went down to the Government mortuary in New Brighton, Port Elizabeth on 29 June, 1985, to identify the bodies of Sparrow and Sicelo. The families were only allowed to see the bodies from a distance, and from behind a glass panel. Both Mhlauli and Mkonto had been handcuffed and tied with rope. Nyameka Goniwe fears that while Sparrow and Sicelo’s bodies were found, Fort and Matthew were still being interrogated. People had scanned the area where their bodies were later found. Where Sparrow and Sicelo were found, there was petrol all around, the bodies were still wet, and there were lots of bloodstains. When Matthew and Fort were found, there were no signs of bloodstains.

Lindelwa and Catherine believe they lost Sicelo’s father prematurely. He was broken by the death of his son. The police did not come to tell them he had been found murdered. He found out with the other activists, and travelled down to PE with them to identify the body. Sicelo’s widow, Mbuyi, tells how he came back talking to himself and “not himself at all”. He died four years later. Sicelo’s mother died in 1995, also of a broken heart. Mbuyi lives with her two children, daughter Babalwa, and son Ntsika. She says she will not forgive under any circumstances.

The funeral was held on July 20, and was addressed by Allan Boesak, Beyers Naude and Steve Tshwete. A message from ANC leader-in-exile Oliver Tambo was read to the tens of thousands of people who gathered. President PW Botha responded with a State of Emergency in the Eastern Cape the next day (the following year it would be extended around the country). Victoria Mxenge, who also spoke at the funeral, was stabbed and murdered 15 days later. The era of Apartheid hit squads had begun.

Mbuyi Mhlauli says that although she learned that her husband was dead relatively soon after he disappeared, it took more than 10 years to find out how and why he had been killed. She also noted that knowing the truth and actually identifying the perpetrators was not necessarily a relief – she now has to overcome her own bitterness and rage.

"I know how it is to lose a loved one – you feel empty, powerless and live with pain all of the time. In our country, we are talking about forgiveness for the sake of the country and national unity. But it is hard to accept."

“All authorities had been silent throughout apartheid. They held a hearing and the families of the victims testified. We told our stories in public in front of the TRC and the commissioners. We were given a fair chance to be listened to. I have been able to share my pain with the country.

Nombuyiselo says the assassins should hang. “Maybe it’s because I am still coping with difficulties in bringing up our two children. But I think they (the killers) deserve it.”

A monument commemorating the lives of three generations of Cradock activists who died during the struggle, including the Cradock Four, was unveiled by Deputy President Jacob Zuma and Eastern Cape Premier Makhenkesi Stofile. Zuma said the "new cadre" the ANC was looking for would be like the four men who had made the "ultimate sacrifice" in the struggle. “To truly honour these fallen heroes we must complete their mission by serving our people and transforming South Africa".

Zuma said that Cradock – and the Eastern Cape as a whole – had provided many of the ANC's "giants" and Cradock in particular had become an "item on the agenda of the apartheid regime". Apart from the Cradock Four, the stone and marble monument topped by a "flame of hope and liberty" was dedicated to nine of Cradock's fallen heroes. They include Jacques Goniwe, Gangathi Hlekani, Lenon Melani and Ben Ngalo, the four Umkhonto we Sizwe activists killed during the Wankie-Sipholilo campaign in Zimbabwe in 1967. It was also erected in memory of Canon James Arthur Calata, the ANC's longest serving secretary-general.

Nearby is a modern steel monument depicting four figures sitting in circle holding hands. Monument designer Christa de Wet said the figures represented the Cradock Four. On the 10th anniversary Madiba and Raymond Mahlaba visited the graves to lay wreaths.

A new monument to the Cradock Four is being built on the hill behind Lingelihle, nearer to their original homes, and where the community of Lingelihle can see it every day. It is also highly visible to anyone travelling on the national road.